09 Aug 2023 The new state of play

By Donna Lampkin Stephens

Logan Horton is the godfather of esports in Arkansas, and he’s got a growing organization.

Horton, 28, was hired as esports coach at Hendrix College in 2020. Hendrix was one of the state’s early collegiate programs, following Henderson State. Others with official teams or interest in building one include Lyon College, Southern Arkansas, Arkansas State, UA-Monticello, John Brown University and the University of Arkansas. Many universities also offer club teams.

A former competitive and sponsored esports player, Horton grew up in Hot Springs and graduated from HSU. While teaching at the Academies of West Memphis in 2017, he looked back to those experiences in an effort to reach his students.

“I needed my students to show up to class,” he said. “A lot of them have what I would call real-world things going on in their lives, so I used some technology things after class to have some video game tournaments, and that was how we created esports.”

According to Bobby Swofford, assistant executive director and esports liaison for the Arkansas Activities Association, more than 110 high schools competed last spring in the various games. Schools can have multiple teams, so overall there were 417 teams with more than 1,900 competitors.

And it’s only going to continue to grow.

“The growth of esports within the Arkansas Activities Association is something that I would have never expected at this rate,” Swofford said. “It is the fastest-growing activity in our state, and it is going to do nothing but continue to skyrocket in popularity.”

After Horton’s experiment launched in West Memphis, he moved to Lake Hamilton, where he built a successful esports program that served 60 students and generated more than $200,000 in scholarship opportunities, according to a Hendrix press release.

“I saw how effective it was at reaching kids who fell through the cracks,” Horton said. “That’s who we’re always trying to reach, and there’s such a large demographic in general who play video games. There are so many kids who wouldn’t have an opportunity to be invested in school spirit otherwise. It’s about school spirit.

“That was my big pitch when I went to Lake Hamilton.”

He said he had bonded with an older brother through video games and saw how they could aid in communication. Teams are recruited for particular video games, usually those with a large spectator base that are based on skill and not on chance.

Swofford said a national survey found that 90 percent of esports competitors are not involved in any other school activity and that those who are involved in at least one have a 99 percent graduation rate — 10 points higher than those who are involved in none.

Horton said his job was different from a coach of a traditional sport. “I’m teaching them a lot of other skills,” he said. “I’m teaching life skills, which is what makes the difference here at this level. What I’m teaching is communication, teamwork and leadership to make players independent and able to handle a lot of pressure. We’ve got big teams, and we have to be communicating.”

After two years at Lake Hamilton, Horton went to Hendrix to start its program.

“We have medaled (finished in the top three) every year in the (Southern Collegiate Athletic Conference),” Horton said. “Last year, we won League of Legends.” While he said the Warriors are “almost never” the best team on paper, they’ve been able to win more than not.

“It’s that level of communication, what these players can communicate to each other, that really turns the tide of how the game is played,” he said.

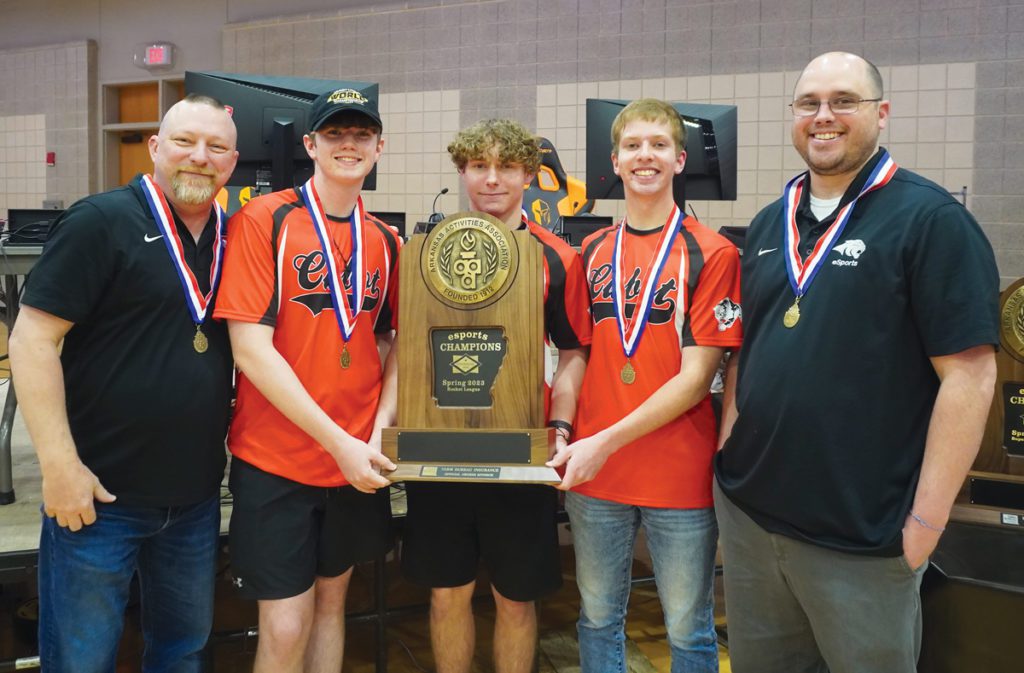

Hendrix hosted the high school state championships last fall and spring, drawing roughly 500 fans and students in the fall. “With more than 1,900 competitors in Arkansas last year, esports is reaching students that other activities have failed to do in the past,” Swofford said. “Students are looking for new and exciting things to be a part of, and this seems to be it.”

Horton said he took pride in that growth. “I have a big list of a couple of hundred coaches in the state now,” he said. “There’s been a lot of opportunity. I’ve gotten to write curriculum, build classes and programs across the state. I got to help build a video game/business degree at Arkansas Baptist College.

“It’s spreading rapidly, not just here but everywhere. Thirty-eight percent of (high) schools in Arkansas now have esports, and it’s crazy to think five or six years ago it didn’t exist at all.”

He said his son, whom he adopted while at Lake Hamilton through the McKinney-Vento Act, was a poster child for the program.

“It was really about the students we might miss and their opportunities,” Horton said. “Honestly, I may tear up a little, but I think my son is a big testament to that. He was in the alternative learning program, a military brat who’d lived all over the world and never had a baseline of what education is supposed to be like.

“All kids learn differently, and he just needed that opportunity, a passion. This was a kid who wasn’t going to graduate from high school, but I got him as a junior, and he made up classes through the summer and graduated on time. He lives in Illinois now, and his entire career has been provided by him finding an online gaming community while he was participating in esports.

“It’s phenomenal, the power of having a passion for something you have a calling for.”

- Fits like a glove - December 2, 2025

- Petit Jean: The place for partnerships - December 1, 2025

- Youth of the Month: Emalee Jack Goforth and Bailey Fournier - November 4, 2025