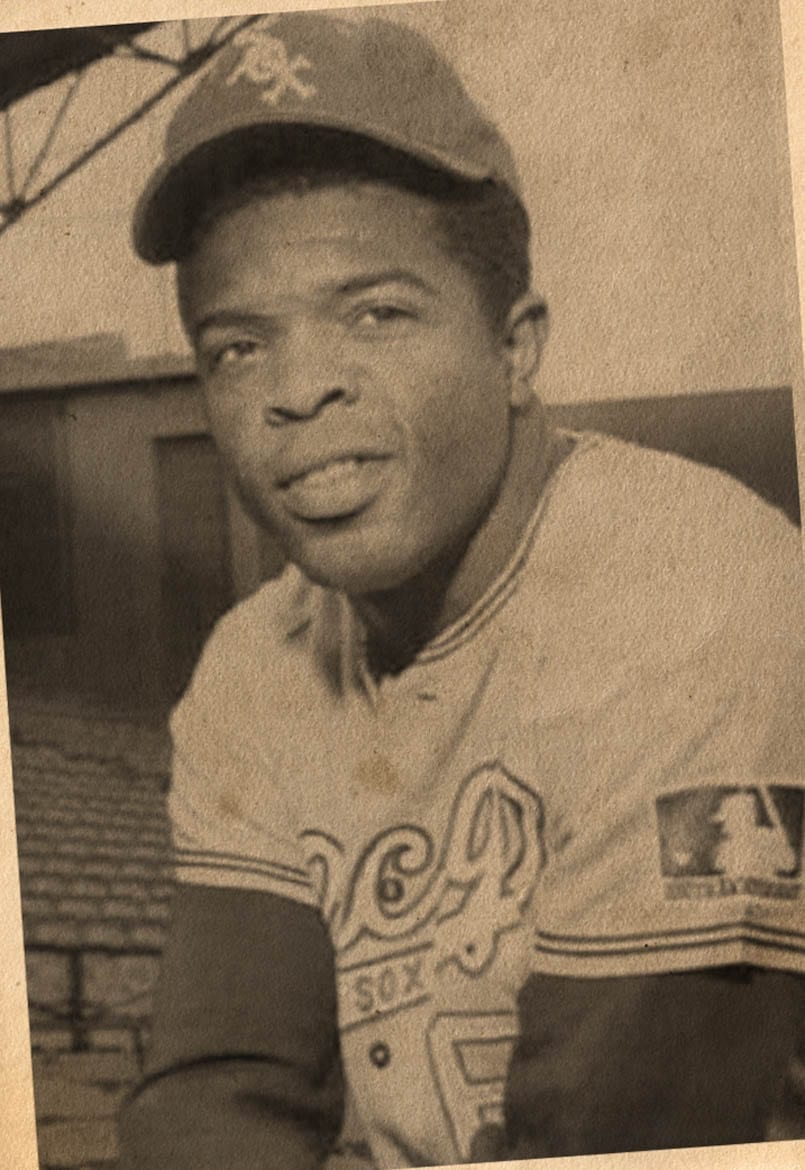

29 Oct 2020 Celebrating Athletic Excellence: Hot Spring County – Tommy McCraw

by Dr. Robert Reising

“I can’t eat trophies,” he politely responded when invited by his high school track coach to join the track team. The speedy teenager added that he wanted to concentrate on money-making sports. His decision, indeed, proved wise.

Today, Tommy McCraw enjoys retirement in Port St. Lucie, Fla., his trophy case adorned by non-eatable trophies won during his 37-year major league baseball career.

Born on Nov. 21, 1940, in Malvern, he learned early to throw and catch a (ragged) baseball. In 1946, Tommy moved to Venice, Calif., with his parents. His mother, a food handler, and his father, a singer, loved their native soil but envisioned, and enjoyed, better financial opportunities in “The Golden State.” Every few years thereafter, Tommy has returned to Malvern for family reunions, and even today he retains ownership of Tatum properties, long held by his mother’s forebears in Hot Spring County.

In 1958, he graduated from Venice High, after starring in basketball as well as baseball. An abbreviated stay in a junior college preceded his signature on a Chicago White Sox contract and entry into professional baseball two years later. Three seasons of minor-league success, including a league batting championship at Indianapolis, the parent club’s most advanced franchise, earned Tommy a place on Chicago’s roster in 1963.

Although his hitting was inconsistent, he quickly proved invaluable because of his defense, speed and versatility. Many an American League (AL) player and manager called him the league’s best-fielding first baseman and one of its most capable base runners and stealers. He also had an extremely important distinction — a rarity in the outfield, he was equally adept in all three fields, left, right and center.

After April 1973 and the arrival of the DH (designated hitter) in the AL, he found yet another role in which he could contribute.

His affable, accommodating personality was always an asset, too. The cry for “Quick Draw McCraw,” a cartoon character popular during his adolescence, never failed to elicit his levity.

During his 13 playing seasons in “The Bigs,” Tommy found his name in full-game box scores more often than in starting line-ups. Only if a regular first baseman or outfielder were slumping, injured or ill would he find himself a starter.

Yet in Chicago, where he performed for eight campaigns, through 1970 he became a fan favorite. Appropriately, Carroll Conklin includes both a photo and a profile of Tommy in his 2013 “White Sox Heroes: Remembering the Chicago White Sox Who Helped Make the 1960s Baseball’s Real Golden Age,” a paperback tribute. Tommy’s most memorable, ingratiating feat in “The Windy City” occurred on May 24, 1967, when he hammered three home runs and narrowly missed a fourth in a romp over the Minnesota Twins; in the same contest, he provided his single-game career high: eight runs batted in.

Ironically, four seasons later, while playing for Washington, Tommy hardly resembled Babe Ruth when providing one of the sport’s most bizarre home runs ever. He circled the bases and earned credit for an inside-the park home run when three Cleveland fielders were knocked out, injured and hospitalized in a futile, collision-causing attempt to catch his 140-foot infield fly.

He played just one season for Washington in 1971. Under Ted Williams, one of the finest batters in baseball history, Tommy admits he learned more about hitting than from any other manager. Statistics validate his belief: post-Williams, 1972 through 1975, he hit his career best, coming within 10 points of the coveted .300 mark in 1974. More significantly, he carried Williams-like beliefs into the second and longer half of his major-league career, 24 seasons as a hitting coach.

No instructor has been more ecstatic with his long-day, late-night responsibilities. He often conceded that he honored the words of wisdom a veteran coach urged upon him early in his coaching days: “Never let a ballplayer beat you to the ballpark and never leave until the last player is gone.”

His post-playing career proved delightful. He viewed himself as a teacher, and once proclaimed to The Sporting News, “I love it.” Never without a job when he sought one, he “excelled,” too, argued prize-winning sportswriter Bruce Markusen eight years after Tommy’s retirement from the game to which he devoted his life.

Presently writing a book on hitting, Tommy refuses to be idle. Hot Spring County and the 501 are proud that he continues to enrich the sport he met on their soils as a youngster.

- Celebrating Athletic Excellence: Saline County’s George Cole - March 31, 2024

- Celebrating Athletic Excellence: Pulaski County’s Anthony Lucas - March 10, 2024

- Celebrating Athletic Excellence: Perry County’s Cali Lankford - February 3, 2024