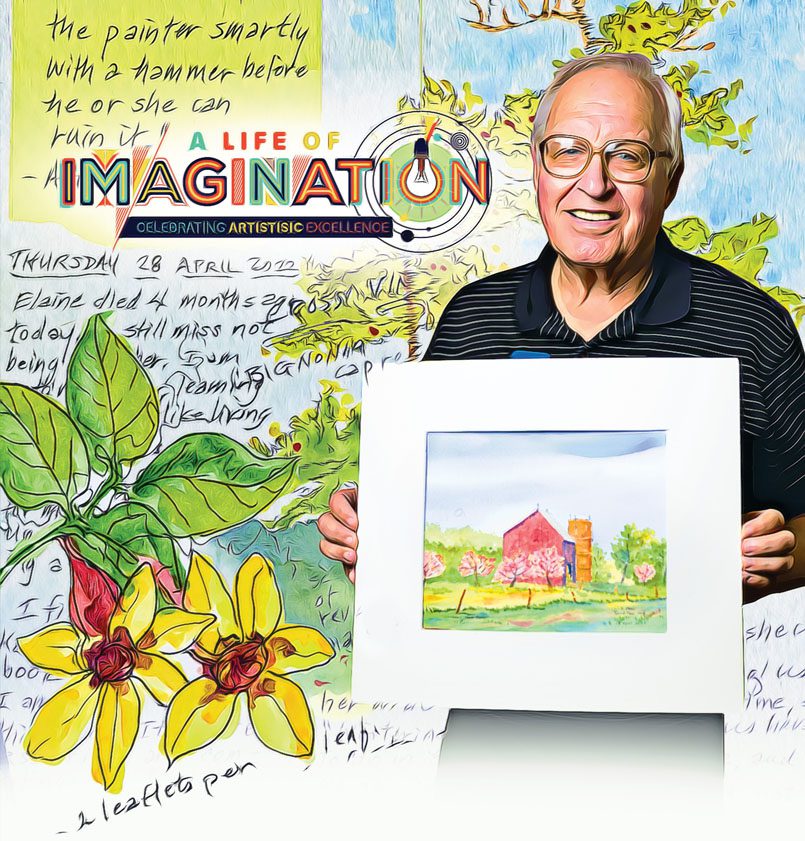

31 May 2022 Celebrating Artistic Excellence: David Paul Cook

By Dwain Hebda

As long as he can remember, David Paul Cook could draw. He could draw just about anything he laid eyes on, in fact, and was rarely seen without pencil and paper during his formative years.

In turn, Cook was drawn to the woods and meadows surrounding his Wisconsin hometown. Nature was all around and brought with her an endless array of subject matter. Shape, texture, color, and shadow, all lie within the sunny vales and cool northern glades.

“I had an interest in art all the way along, as you might have imagined,” he said. “As I got older, I wanted to explore things further. I discovered my public library and realized that they had all kinds of books available on drawing and painting. So, I became a regular visitor there.

“One day, I went into my local public library and there was a display of watercolor paintings, landscapes, that were done by somebody in my town. It was a thunderclap, because I realized here was somebody from my part of the world who was producing art. Suddenly, I had license to be an artist myself.”

Cook’s parents, noticing his ambition and interest, enrolled him in weekend art classes and his talent blossomed. By the time he got out of high school and headed to the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, he was curious to see where the next step on his path was going to lead.

“I arrived for freshman year and signed up for some art classes, and I enjoyed them,” he said. “But I knew that sometime in my future I would be married and have to be responsible for feeding a family. As I looked at all the other students who were there, I saw them, unfortunately, as competitors. I asked myself was I good enough that I could make enough money to feed a family. I came to the conclusion that I was not.”

Cook’s decision might have been altered had he received some guidance in college as to the many professional avenues that existed for someone with talent such as his. Lacking that advice, he found another professional path that let him stay connected with nature.

“I had an advisor interested in biology, and I had an interest in plants and animals,” Cook said. “He told me, ‘Well, if you’re not going to pursue this art thing, why don’t we have you go in the direction of botany and zoology?’ So, my bachelor’s degree is in biological conservation, which was a combination of botany and zoology.”

After earning his master’s degree, Cook took a job with the University of Wisconsin Extension in Milwaukee, working on environmental affairs. As a voice for the wilderness, he hosted a weekly environmental affairs program for public television and public radio.

Pollution is a big concern in environmental circles, as it is for the organizations dealing with its harmful effects. In time, Cook would join the American Lung Association, which took him to Kansas City and then to Little Rock in 1985. And wherever his professional and personal mission led him, he brought his artist’s eye along for the ride, translating in his free time what he’d seen out in the wilds.

“I continued to paint and draw for myself from that point forward, as much as a person can when they’re earning a living doing other kinds of work,” he said. “When I got to retirement in the year 2000, I realized that if I didn’t do something about my interest in art that it would probably wither and dry up and blow away.”

“I decided to do something every day for 20 minutes that was artful. It didn’t necessarily have to be drawing or painting; it could be visiting an art museum or going to an art gallery or reading an art book or magazine or talking to other people who were artists. In order to keep track of that, I bought myself a journal, and I started writing down what I had done that day that was artful.”

Cook’s journals became a primary canvas. Resembling the field journals of the great naturalists, his books explode with colorful illustrations of natural scenes and specimens of flora and fauna. The notebooks chronicle his vision in word, image and assembled artifacts, and even as he works on the 41st of them he’s still never at a loss for inspiration.

“In creating things with pen or pencil or ink or brush you can’t do everything,” he said. “You have to be selective in terms of what you’re doing. And you can’t stay in one spot forever. You have to get it said, and what that means is that you really have to look at what you’re doing and appreciate the ins and outs of it.”

Making connections with various guilds, such as the Conway League of Artists, Arkansas League of Artists and Mid Southern Watercolorists, befriended him to like-minded artists, furthering his craft. He’s even helped to bring artistic talent to the surface via teaching stints at the Maumelle Senior Center and the Museum School of the Arkansas Arts Center (now Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts) in Little Rock.

Teaching provides an intersection of art and community that he finds priceless, not just for himself, but for the awakening his students’ experience.

“I encourage people to know that the water is warm and refreshing and I hope that they would start splashing, because we learn by doing,” he said. “I would encourage them never to compare themselves with anybody else. If they are doing something that they enjoy doing, and they are turning themselves from being a looker into a seer, I can guarantee that their life is going to be much richer with that as a pursuit in their life.

“We live in a beautiful world, and I hope everybody can enjoy it at the level and beyond the level that I have. It makes the world much more inviting than if you’re just looking and not necessarily seeing.”

- Conway couple called to serve foster children, families - March 10, 2024

- Artist of the Month: Terri R. Taylor - November 5, 2023

- Everybody loves a nut - November 5, 2023