31 Jan 2022 The Family Circus

By Dwain Hebda

Tosca Zoppé was born to be a circus performer as part of Zoppé Circus, a family business spanning nearly 200 years.

“It’s always been my life,” she said of the performance art form. “I’ve always loved it.”

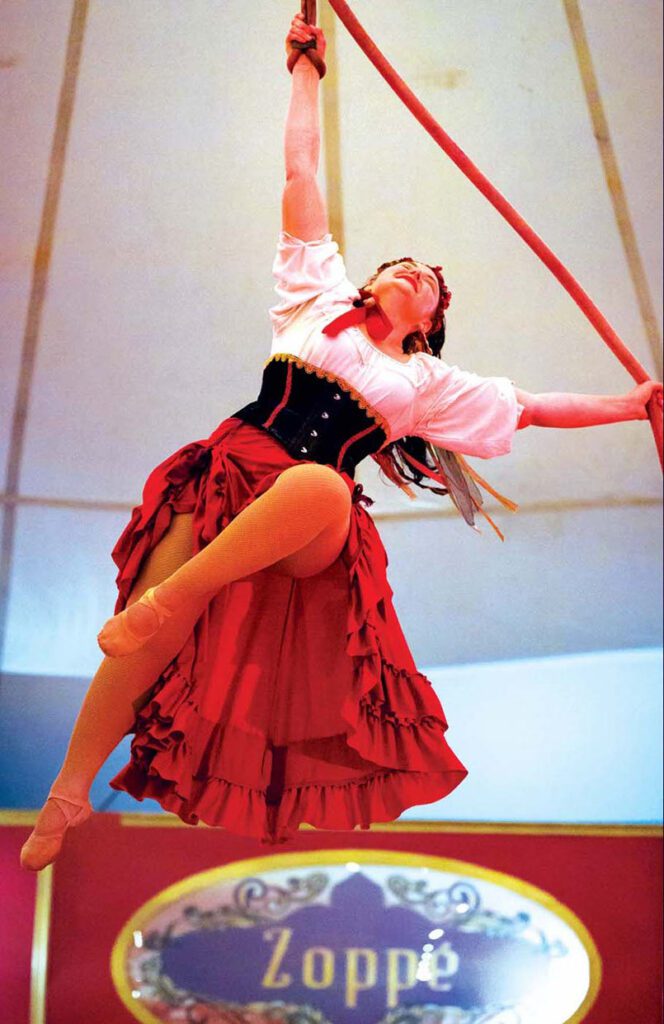

Practically from the time she could walk, Toske Zoppé was a tiny ballerina in the circus’s signature equestrian act, something for which she showed natural artistry and expertise as she grew. A few years ago, when she launched her own production, Piccolo Zoppé, horses remained the centerpiece of a show that also includes aerialists, wire acts, and clowns.

Piccolo Zoppé keeps alive a brand of circus much different from what American audiences are used to. Instead of behemoth three-ring versions that typically play major auditoriums, the Zoppé circus has always been smaller, one-ring shows cast in the classic European tradition. Zoppé took that philosophy even further in Piccolo Zoppé, providing an intimate evening of entertainment that connects with audiences in ways that larger circuses cannot.

As with all live entertainment, COVID-19 cut performances to near nothing in 2020, but performances rebounded to 11 cities and 132 shows in 2021. Zoppé said she would like to build Piccolo Zoppé’s schedule to encompass 25-30 weeks in the coming years. She’s also passionate about preserving the circus arts for future generations, having launched an all-ages circus camp.

“The whole circus school experience has really exploded in the United States,” she said. “We started doing bareback riding camps for kids about 15 or 16 years ago across the country. It was a natural progression to our full circus camp four years ago. They learn how to ride, they learn a little bit of aerial, clowning, juggling, tumbling, a little bit of everything. And at the end of the week, it all culminates in a show they get to share with family and friends.”

Both the show and the camp are Zoppé’s way of paying tribute to the history of the art form and her family’s role in it. In a profession that’s easy to romanticize, the true origins of the Zoppé Circus is something to behold. Commencing in 1842, a young, French street performer, Napoline Zoppé, spotted Ermenegilda, a beautiful, equestrian ballerina in a Bucharest Plaza. Ermenegilda’s father disapproved, dismissing Napoline as a lowly clown, so the young lovers ran away to Venice where they founded their circus.

A century later, with the couple’s great-great-grandson, Alberto, and his siblings taking their places in the family business, the company struggled through the devastation of World War II bombings that decimated their livestock. Despite this, Zoppé Circus remained a draw, particularly for one well-known American film icon.

“Orson Welles used to visit our family’s circus in Italy quite a bit,” Zoppé said. “For one, he loved the circus, and he was friends with my father. And he really loved my grandmother’s cooking.”

Welles talked Alberto into coming to London to appear in a movie about the circus and arranged an introduction between the Zoppé family and John Ringling North of Ringling Brothers, Barnum and Bailey Circus. He also lobbied Alberto to come to America to appear in Cecil B. Demille’s film, “The Greatest Show on Earth.” The patriarch balked at the idea, saying his family’s business would likely not survive his absence.

After some thought, Alberto made a counter-offer. If Ringling Brothers would loan Zoppé Circus one of their elephants — an almost unheard-of attraction among smaller European circuses at that time — it would provide enough of a draw that Alberto and his family would come to the U.S. for the project. After some wrangling, a deal was struck and so began the family’s American chapter in 1948.

Born into the life of a circus troupe meant Zoppé’s upbringing was at best unconventional and replete with animals many people only see in zoos. At three days old, she took her first elephant ride, and as a tot, she was tended side-by-side with a lion cub.

“The day I was born, my father wasn’t at the hospital because he was helping my uncle deliver lion cubs. My uncle gave him one of the cubs,” Zoppé said. “I was actually raised with a lioness that was the same age I was. My mother would prepare two bottles and feed both of us in the back of a station wagon. She painted the lioness’s bottle gold so she’d know which was which.”

As a child of the circus, Zoppé lived a nomadic life filled with homeschooling, performing, and never staying in one place for long. That is, until one day her mother put her foot down. “Mom had had it. We’d spent a lot of time in an RV, and she wanted to have a home she could go to that was actually a home,” she said. “We’d rented a farm in Little Rock for the winter because it was centrally located and we were doing a lot of performances across the South. One day she said, ‘I’m going to go look for a house.’ She found it in Greenbrier.”

Greenbrier native Max Young II said it was a magical piece of his growing up to spend time with the unique family.

“I was five years old when the circus moved in across the street,” said Young, who estimates he’s seen 50 Zoppé performances overall. “It changed my life and shaped my life. They brought culture and people from all over the world into a place where I was starved for those things. They really helped me reshape my whole image and outlook of this world and what life is like for people around the world. They were highly impactful on me.”

Even after calling Arkansas home for 30 years, Zoppé and her band are still very well-kept secrets in The Natural State. Piccolo Zoppé recently performed in Greenbrier for the first time ever and Zoppé’s eager to expose more Arkansans to the art form she loves so much.

“I have a passion for our history and our heritage, honoring those who went before me,” she said. “To share that with people is really our biggest love and biggest joy.”

- The pinnacle of success - June 1, 2025

- Five-Oh-Ones to Watch 2025: Aaron Farris - December 31, 2024

- Julia Gaffney brings medals and mettle home to Mayflower - October 30, 2024