10 Aug 2025 Lessons of a lifetime

By Vivian Lawson Hogue

My first-grade experience was what I hoped it would be. My first six years had been spent around my four brothers and neighbor boys from the Brannan, Spatz and Malpica families. I could hardly wait for my turn to go to school where there would be other girls. My parents couldn’t afford to pay for kindergarten, so it was just “me, myself and I” until school age. We three got along well, though.

After another year, school held good times, such as playing jacks, pick-up sticks, hanging upside down on the monkey bars, smelling crayons and pencils and the linseed oil on the old wooden floors. Open windows brought in the aromas of burning trash from paper, limbs from the playground and leaves in the fall.

One day, we had an impromptu writing lesson. Mother had bought a coat for me, and I was ecstatic because most of my clothes were homemade. It was burgundy with a hood. I mentioned it so many times that our teacher, Mrs. Sharp, had everyone get a sheet of Big Chief paper and write “Vivian’s New Coat” at the top of the page.

We were to describe it and say something nice about it. I can’t express what it did for my ego! It also shut me up. Arithmetic was next, though, and my ego was deflated again. In fact, this condition returned during all math classes until I received my college degree in, of all things, education.

Through the years, I became interested in how education began in America. This was partly because of the one-room schoolhouses in which my parents taught. They were born in the turn of the century in 1900 and 1901, so I was privileged to know details.

It always seemed important for society to have knowledge. The value of early educational environments would progress to local governing districts and teacher qualifications. Out of them would eventually come the titans of business, education, medicine, invention, art, sports, farming and churches. In fact, churches were often classroom locations until a school could be built.

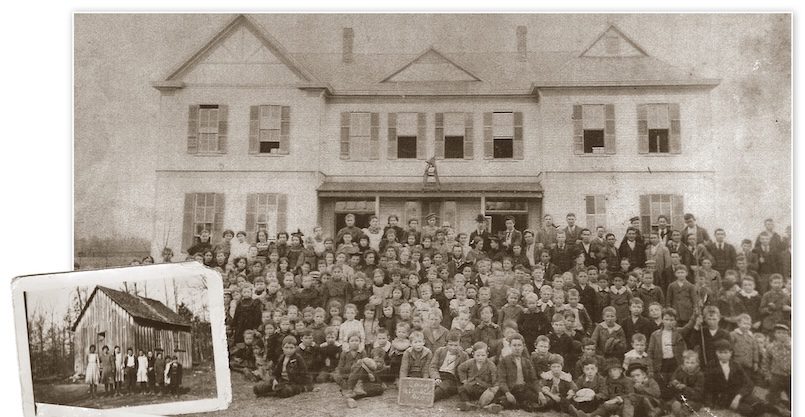

Early schools were typical in design and function. Most were frame or log structures with the exception of some fortunate enough to have rock sources. There was a front door and two or three windows on each side. Students faced a blackboard, which was normally a smooth wall surface painted black.

During spelling bees, each student stood at a chalk line on the floor and misspellers would have to move to the last line and work back up (thus the phrase “toe the line”). Competitive spelling bees sometimes created great rivalry between schools.

Deskwork writing was done on slate tablets with slate pencils. My mother’s 119-year-old slate is about the size of notebook paper. Students erased using a damp cloth or well-aimed spit and a shirt-sleeve (thus the phrase “start with a clean slate”). The two genders sat on opposite sides of the room, and recess games were often played in male and female groups, which they preferred.

With no need for custodians, daily upkeep was done by the teacher and students. They carried wood for the wood stove, added wood and stoked the fire, refilled the water bucket, and dusted. A bucket of water and dipper for drinking was at the back of the room, with everyone drinking from the same dipper. Indoor restrooms were nonexistent, but somewhere downwind there was an outhouse.

By 1900, teachers were highly regarded in the communities, although their pay did not reflect the prestige! They often lived with local families, so their $25 monthly salaries disappeared quickly. Both of my parents taught in schools like these, instructing grades 1 through 8 in reading, printing and cursive writing, and arithmetic. Older students up to age 21 studied classic literature and Latin. My siblings and I were grateful to have absorbed some Latin from our parents.

So how does this history fit into Faulkner County? Easily, because many of these descriptions match its own country-school histories. All of its small county schools were eventually consolidated with “larger” nearby towns of Greenbrier, Conway, Vilonia, Mayflower, Mount Vernon, Guy-Perkins and Enola. By 1873, several county school buildings had been built to accommodate both white and black children.

The first public school in Conway was located on Locust Avenue and North Street in 1879. A larger one was built in 1893 at Davis and Prince streets. A two-story red brick building replaced it in 1909. A new white brick senior high was built in 1937. The Ellen Smith school was built on Harkrider in 1925, and Pine Street school was constructed in 1952.

From these strong roots, it is no wonder that three colleges were located in Conway, Arkansas, a town which gained the nickname “Little Athens.” While we didn’t expect that era, we will never forget our own Dick, Jane, their dog, Spot, and Puff the cat. See them run, run, run!

- They found their ‘true grit’ - January 5, 2026

- And that’s what Christmas is really all about - December 2, 2025

- Giving thanks - November 4, 2025