09 Oct 2023 Hay, what’s going on?

By Judy Riley

A common sight in Central Arkansas is a truck and trailer loaded with hay each fall. Those large bales, most often round ones, will feed livestock, primarily cattle. Do not mistake this scene as merely part of a pictorial country landscape because hay production is big business in the 501. According to recent statistics, more than 1,093,000 acres produces 2,188,000 tons of hay bales for a value of $290,000,000 statewide. Much of that is in Central Arkansas.

Not all hay is the same. The bale of straw decorating our porches in the fall is different from the hay the cows eat, much less the more refined hay for horses.

“A variety of grasses are used for hay, but in Arkansas, Bermudagrass is king,” said Brian Haller, Staff Chair and Agriculture Agent for White County. “Other grasses include bahiagrass, dallisgrass, fescue, ryegrass and native mixed grasses. Straw is a byproduct of wheat and other small grain production and is used not only as décor, but for land prep in construction.”

Hay is generally used to feed livestock, which includes cattle, sheep and goats, all referred to as ruminants. A cow’s digestive system is fascinating, uniquely qualifying them to use high roughage feedstuffs efficiently. Any teenager’s parents may think they have four stomachs as they cannot seem to get enough to eat. But cows really do have four stomachs, better known as four compartments of one stomach! Cows graze by first wrapping their tongues around plants, then pulling to tear the forage with their bottom teeth. Cows have no upper teeth. On average, cattle take from 25,000 to more than 40,000 bites each day. The partially chewed food goes first through the esophagus, which allows them to regurgitate the food for further chewing, a process known as “chewing their cud.” The food moves through all compartments and is broken down further. The largest stomach compartment of a mature cow can hold up to 40 gallons.

Hay provides protein, energy and fiber to livestock diets. A cow will eat hay only five months a year and graze grass the remainder. That equates to a bale a month, which is about 4,500 pounds per cow per year. They typically spend more than one-third of their time grazing, one-third chewing and the remaining time idling.

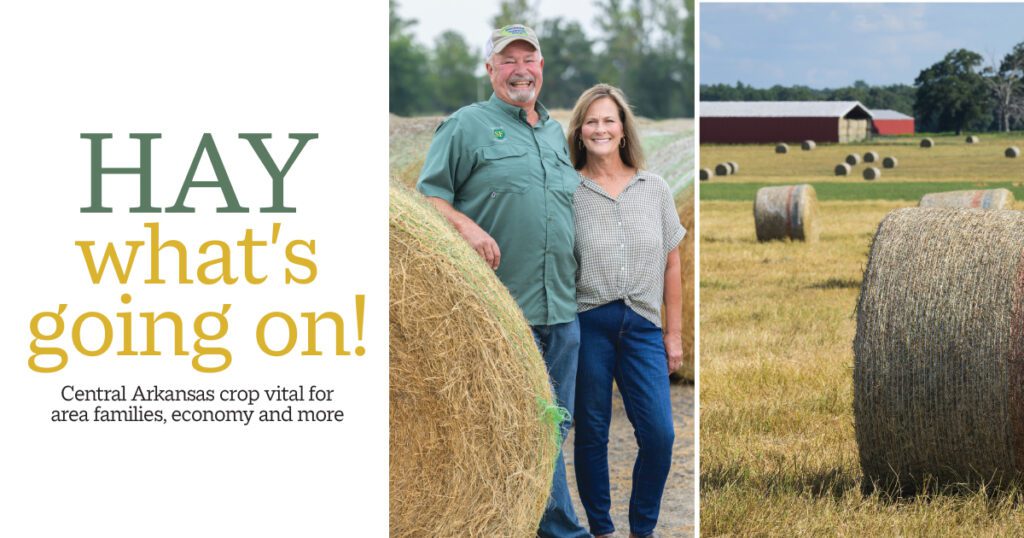

“Most hay is produced on family farms,” Haller said. “Some farmers do their own hay baling. Others hire it done as a percentage of the value.” One unique farm family is Larry and Belinda Shook of McRae in White County.

Larry grew up on a row crop farm that included rice, soybeans, wheat, corn, cattle and chickens. He started farming on his own in the worst possible year, 1980. After a severe drought, Larry began work as a North Little Rock Fireman. He could manage the farming operation in his off time with that work schedule. He saw the need for good quality hay and started small, like most farmers. He began with 40 acres of Bermudagrass. From that humble beginning, he now farms 1,600 acres with 800 acres in Bermudagrass.

Larry saw the need for high-quality hay which is primarily used for horses because their upper and lower teeth enable them to eat differently. Horses have only one stomach and are not considered ruminants. They do not have the luxury of a four-compartment stomach, so they do not do as well with the high fibers tolerated by cows. “We produce about 100,000 small, square bales a year,” Larry said. “They are sold to 20 plus farm supply stores, the Little Rock Zoo, several riding and horse training facilities and regular customers. Bales are packaged in bundles of 21 bales and are sold as a bundle, making it easier to transport. When we sell to a farm store, we typically fill an enclosed trailer, deliver to the store, and pick up an empty trailer.”

For the Shooks, farming is a family endeavor. In the early years, Belinda did all the record-keeping and could often be found on a tractor. As her career in education became increasingly demanding, she turned that over to her daughter-in-law, Lauren. Their son, Matt, helps with the family farm when needed, but he and Lauren have an erosion control business, using straw and lesser-quality hay in highway construction. Daughter Martie helped with the farm as a teen, tending the sale of sweet corn. She is now an educator in the Cabot school system. Larry’s dad, Stanley, once a full-time farmer, cannot seem to escape the family business. At 87, he still helps to bring hay wagons to the barn. According to Larry, he can often be spotted in his truck, driving around and checking on things.

When asked about his biggest challenge, Larry said, “As with any farmer, it is the weather, but especially so with hay.” The process requires a lot of planning, usually three days in advance. When the weather does not cooperate and it rains unexpectedly, it can create less quality hay. When that happens, instead of hay being baled in small, square bales for horses, it is baled in large round bales for cattle or construction use, according to Larry. The phrase, ‘make hay while the sun shines’ rings true.

Both Larry and Belinda retired in 2019, Larry as a North Little Rock Firefighter and Belinda as Superintendent of Beebe Public Schools. Now, as full-time farmers, they would not trade their lives for anything. Having the opportunity to work with Larry’s dad, their children and grandchildren is a rare gift. After all, it is ‘the family business.’