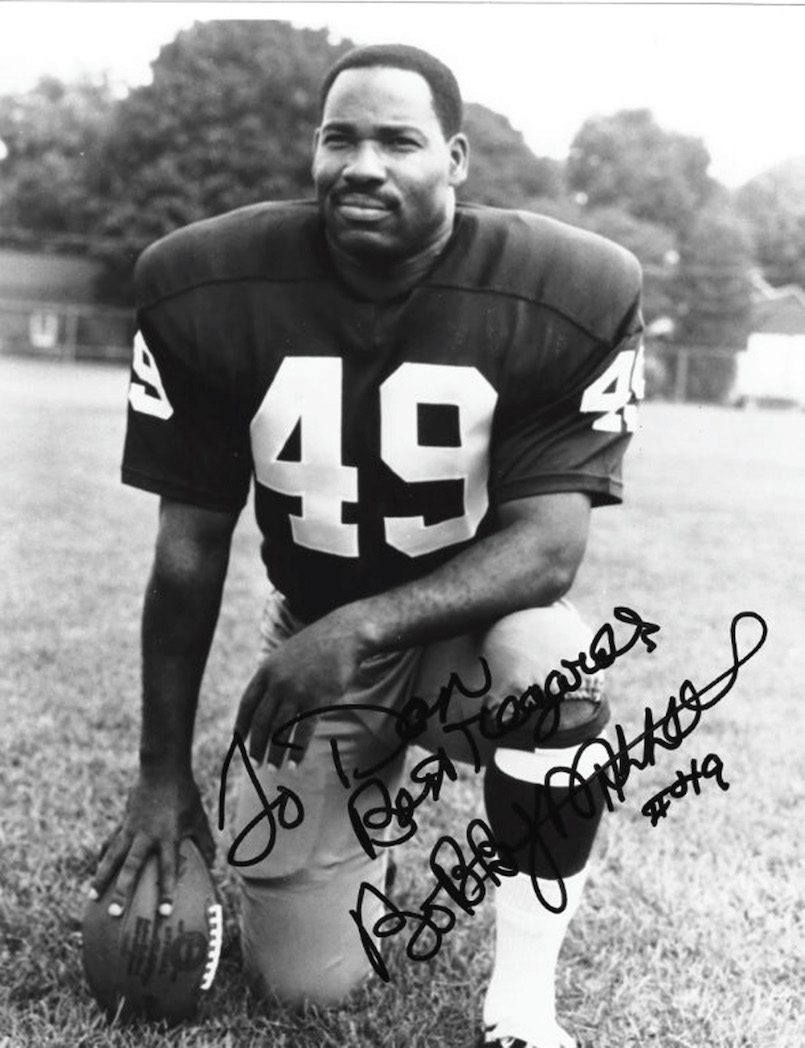

24 Sep 2018 Garland County: Bobby Mitchell

by Dr. Robert Reising

During his 83 years, Robert Cornelius Mitchell has attracted many nicknames and labels. To his family while growing up in Hot Springs, he was Neal; to fans in the same city marveling at his high school football scoring, “Mr. Touchdown.” To a sportswriter describing his first-game performance at the University of Illinois, he was “a star falling out of heaven”; and to the Cleveland Browns of the National Football League (NFL), “Mr. Outside” and “Mitchell the Missile.” But to longtime friend Don Duren, he was simply “The Remarkable Bobby Mitchell.”

And remarkable he was and remains. Although continuing to live in Washington, D.C., with his wife of 60 years after retiring from professional play in 1969 and from his post as assistant general manager for Washington in 2003, he is quick to cite his pride in his native city. “I’m proud, proud to say I’m from Hot Springs, Ark.,” he proclaimed in 1997 on one of his infrequent visits back to the city where his remarkable, never-to-be-replicated story began.

The son of a part-time minister, Bobby was a middle child in a family of eight children, and realized early that he had to fend for himself. Athletics became his haven, and he was soon noticed for his beyond-the-norm skills. Soon, too, he became friends with African-American baseball players visiting the Spa City during their off-seasons. The influence of stars like Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella was inestimable, Bobby was later to admit. “Campy” even bought him the suit of clothes he wore to his 1954 graduation from segregated Langston High School, where he was a four-sport star and had twice gained all-state honors in football.

Those baseball greats, however, could help him little in untangling the many options he had for gaining an undergraduate education. For guidance, he wisely turned to his common-sense mother and his life-long friend, Charles Butler, an older, football-playing Langston alumnus. The pair convinced Bobby not to attend the institution he preferred, all-black Grambling University, nor to acquire yet another label, “the first black football player at the University of Arkansas”; instead, they persuaded him to join Butler at the University of Illinois.

His first two years on the Big Ten campus proved painful. Bobby quickly learned that Champaign and Urbana were no Hot Springs — that the respect and civility he enjoyed in his native city were not readily discernible in the Twin Cities. Only after he had exploded for more than 500 yards in the final three Illini gridiron contests of 1955 and, too, after an alert University dean had transferred him from the old Army barracks housing black athletes to an all-white dormitory, did Bobby feel comfortable in his adopted state.

The following season was marred by a knee injury, and his final one by a growing belief that his future lay with track and the 1960 Olympiad rather than football. Although in both years named to the Big Ten’s All-Conference Football Team, he concluded that those honors paled by comparison with his All-Big Ten record-breaking achievements in track. But his mind was changed Aug. 15, 1958, when, before 70,000 fans at Soldier Field in Chicago, he earned Co-Most Valuable Player honors in the College All-Star game after catching five passes for 145 yards and two touchdowns. Within weeks, drafted in the seventh round, Bobby had signed an attractive contract with the Cleveland Browns.

Thus, he embarked on one of the most remarkable playing careers in NFL history, 11 seasons long — four with the Browns, as a running back (1958-1961); and seven with Washington, as a wide receiver (1962-1968). During the 11, he claimed 14,078 combination net yards, 521 pass receptions and 91 touchdowns (eight on kick-off returns!) while earning a spot on three All-NFL Teams and in four Pro Bowls after selection as the 1958 NFL Rookie of the Year.

Subsequent honors included induction into the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame, which hailed him as “the first African-American to play for Washington,” and six years later, in 1983, the NFL Hall of Fame. Introducing Bobby at the latter, Edward Bennett Williams, co-owner of Washington, paid tribute not merely to his playing feats but also to his countless successes in raising millions for benevolent causes throughout the nation: “No one surpassed him in character, in courage, in dignity and in integrity.”

Clearly, Hot Springs, Garland County and the 501 all share the pride in “The Remarkable Bobby Mitchell.”