29 Sep 2022 Conway’s creative couple

By Dwain Hebda

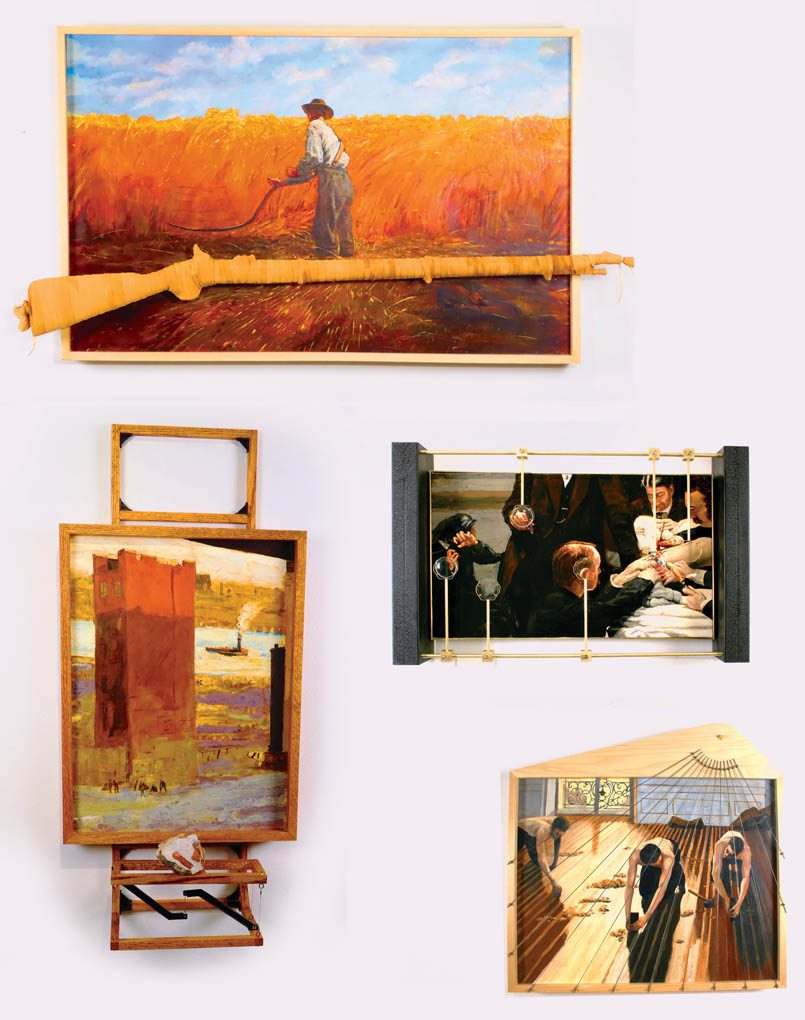

Jim Volkert – A Matter of Perspective

His creations are a wonder of ingenuity and creative thought. His unique perspective marries fine painting in the style of history’s great masters with related physical elements that lend depth and dimension to the overall work. Art, science, mathematics, sports and nature all peacefully coexist in thought-provoking unison, by turn clever and poignant, the product of Volkert’s storyteller philosophy of beauty interconnecting all things.

“I guess I would call myself a presenter. I don’t know how else to describe it,” he said. “I’m taking this element and that element and I’m putting them together and then you, the viewer, sort of pick what avenue allows you to move into the piece, whether it’s the craftsmanship or whether it’s the painting.

“The idea of coming at art from several different points of view really interests me. The idea of combining more than one avenue for the visitor, whether it’s the movement or the words or the enigma of an object, is sort of the common point with whoever is looking at it. That gives them an entry.”

Volkert’s innovative vision was decades in the making. Growing up in Minnesota, he was inspired to follow his vision by a high school art teacher. From there, he attended the University of California-Davis fine arts program, then earned a graduate degree in painting from the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, convinced he was meant to make his living producing art. But life after graduate school held a rude awakening.

“I’d decided I was going to try and make a career of being an artist, but as a young guy without a lot of experience it didn’t work out so well,” he said. “I had a gallery and didn’t sell a single thing.”

Volkert found his way into the museum world, with early positions in Los Angeles and the emerging world of children’s art museums. There, he found ample outlet for his creativity, putting together interactive exhibits that moved guests from mere spectators to engaged participants.

“I really had great freedom to put together exhibitions on whatever interested me and then figure out ways to engage children and young people with the ideas,” he said. “That really led to this notion of you can combine both fine art and other avenues of engagement in mechanisms and interaction and those sorts of things. It invited participation from the kids, the parents and the visitors.”

Each job he held opened doors to new opportunities, including being in charge of exhibitions design for the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian Museum of Art in Washington D.C. in the late 1980s and as Associate Director of Exhibitions of the National Museum of the American Indian, also part of the Smithsonian, starting in 1990.

“That museum had been enabled by Congress, but it was still just an idea,” he said. “I worked there 15 years, opening a museum in New York which is still there as a satellite museum of the National Museum, and then building and opening a collections facility outside of Washington D.C. We moved a collection of a million objects from New York to Washington and then opened on The Mall in Washington, D.C. That carried me right up to retirement in 2005.”

Throughout Volkert’s career, the idea of making art again was always in his head, but the demands of his work left little time to create. Upon his retirement, his wife of 20 years Barbara Satterfield pulled the pin, setting off a creative explosion that continues to reverberate to this day.

“After I met Barbara, retired from the Smithsonian and moved to Conway, she said, ‘You ought to start painting again,’ and bought me a brush,” he said. “And I thought, ‘You know? I ought to.’ Since then, I’ve been making art.”

Between his creations – which incorporate everything from bottles of water from the Jordan River to earth from a New Mexico desert – and his museum consulting, Volkert is in high demand. In 2018-19 he served as senior consultant to the Maidan Museum in Kiev, Ukraine, and has conducted workshops for the National Museum Wales in Caernarvon, Wales, and the Glasgow Museum of Art in Glasgow, Scotland, to name a couple. Everywhere he goes, he sees another story to tell, something to be translated and put on display for the enjoyment of others.

“I try to make art that’s well-crafted,” he said. “The idea of precision and the idea of it being right, is central to what I produce. On the one hand, it’s truth. On the other hand, it’s a fabrication. That dilemma is what’s interesting to me in those pieces.”

Barbara Satterfield – From earth to art

Her artistic journey is not unlike the art she creates. An accomplished producer of contemporary ceramics and sculpture, her creations start as a simple lump of clay that time, motion and skill transform into beautiful pieces evoking contemplation and discussion.

The same can be said of the artist herself, who spent her life feeding an appetite for creativity and beauty in ways formal and informal.

“We moved to Conway when I was 8 in 1960,” she said. “We didn’t have art in public schools in Arkansas at that time. But we did have volunteer groups, such as the Conway Junior Auxiliary and the colleges that did periodic art workshops for kids in Conway. I was very fortunate my parents made sure I got to attend those.”

Satterfield’s first formal immersion in the arts came at Hendrix College, where she earned a theater degree with a particular aptitude for designing and building sets, lighting schemes and costumes. From there came the demands of marriage and family life, leaving her to direct her artistic talents wherever she could.

“After we had children, my artistic expression came, as it does for many young women, through quilting, cross-stitch, smocking and gardening, those kinds of expressive things,” she said. “It certainly was not formal art training; however, I did have the opportunity to open an arts program for children. It was called The Art Station, and it was an old gas station that we renovated so we could have plays and art instruction in downtown Conway.”

When her children went to college, Satterfield decided the time had finally come to formalize her art education. At the University of Central Arkansas, she earned a Bachelor of Arts in studio ceramics, followed by a Master of Fine Arts at George Washington University in Washington, D.C.

Though her training included exposure to many different mediums, ceramics was love at first spin.

“The minute I picked up that clay, I just loved it,” she said. “I just loved everything about it – how it felt, how it smelled, how it transformed from being very soft and pliable to this amazing object that could last centuries.”

Satterfield didn’t immediately leverage her talent as a career, instead taking a job as director of UCA’s art gallery with additional duties as an educator. Upon her retirement in 2011, she continued to build an exhibit resume, including numerous works shown in the 2012 THEA Foundation Arts Festival in North Little Rock.

Today, she continues to find inspiration in nature, which has played a consistently pivotal role in her ceramics, even as finishes and designs change with time and collection.

“My father grew up on a Missouri farm, and wherever we lived, he had a big garden,” she said. “He and I loved to work the garden, plant flowers, be outside, earth in our hands. I think that was an early influence on my artistic interests. As I matured, I found myself drawn to looking at nature, hiking, walking through the woods, noticing things growing, things that slither, things that crawl. Nature’s design is so efficient and so beautiful.”

She also derives considerable benefit from being married to fellow artist Jim Volkert for the past 20 years.

“We’re really good about helping each other solve problems,” she said. “Sometimes, I’m making an installation and I’m not sure how it should be presented or if there’s a particular way I can secure a piece. He’s very good about that. We have found we can talk in shorthand because we reference so many common interests and so many experiences. It’s wonderful.”

- The pinnacle of success - June 1, 2025

- Five-Oh-Ones to Watch 2025: Aaron Farris - December 31, 2024

- Julia Gaffney brings medals and mettle home to Mayflower - October 30, 2024