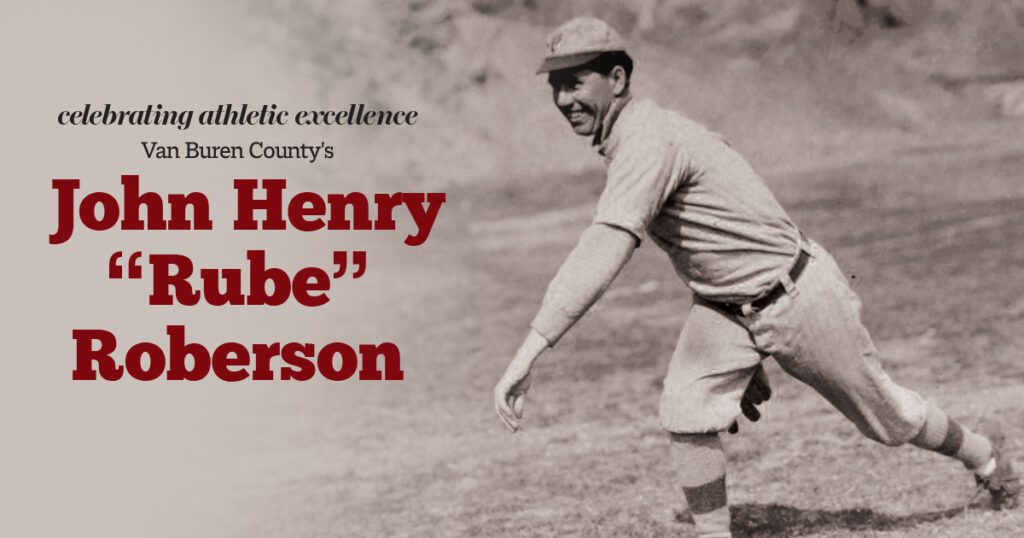

02 Jun 2024 Celebrating Athletic Excellence: Van Buren County’s John Henry ‘Rube’ Roberson

By Dr. Robert Reising

The confusion about his name only adds to his unvarnished, enigmatic charm. Affiliated baseball has seen few performers with more talent, more moxie, or more staying power. A Rube he was—an unflattering nickname to which he never objected—but a Rube who knew himself, the sport he played, and the fans who adored it with him. “The National Pastime” will never see John Henry “Rube” Robinson’s like again.

Little is known about his parents, Joseph Allen and Isabelle Stroud Roberson; his birth on or around August 16, 1889; or his earliest years in White County. Yet, obviously planted were the seeds of his lifelong love affair with baseball and the Natural State.

His affection for the home-grown amenities of rural Arkansas was as evident as his skill at propelling a baseball at various, often eye-catching speeds, occasionally with movement sideways and/or downward. In 1908, the left-hander emerged from Floyd and anonymity to garner 11 victories and only four defeats in two of Arkansas’s Class D professional leagues. His march to 329 professional wins had begun.

That journey was to end 21 years later, in 1929 in Little Rock, where he won 190 of his games, an all-time franchise record. One biographer notes that “Little Rock was perfect for him because it was so close to home.”

And “close to home” he placed himself during the bulk of his playing days, thanks to his ingenuity and a simple plan which he worked to perfection. Despite the then-common “reserve clause” that tied a player to the team owning his contract, Rube would announce that he was leaving to return to his farm, mentioning no professional play. Once free, he allowed homesickness to relocate him to a “near home” team needing pitching help. Delighted to gain his considerable services, that team—if forced—would happily pay a few dollars to the “owning” franchise.

Rube was no fan of the reserve clause; he hated the idea of being “owned.” In 1975, ten years after his passing, the whole of baseball was to agree with him, to see the clause as unfair, and to discard it. Thereafter, players no longer needed to view themselves as chattel; like Rube, they deserved—and gained—a voice in determining where their baseball futures might lie.

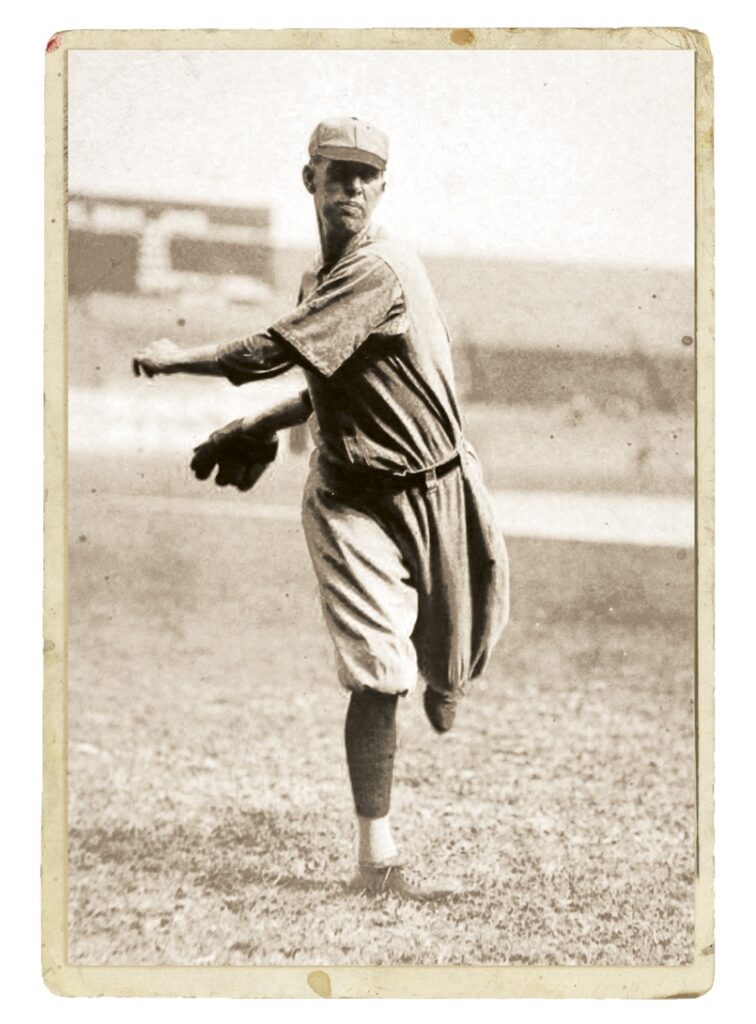

Although no beneficiary of the reserve clause’s disappearance, Rube refused to risk rotting in baseball’s minor leagues. In 1911, after winning a career-high 28 games for Fort Worth’s Class B Texas League franchise, he toed the rubber and posted an impressive 2.77 Earned-Run-Average (ERA) in five games for the National League’s Pittsburgh Pirates. Just three seasons into his professional career, at age 23, he was pitching at baseball’s highest level.

The following pair of seasons proved he could star in “The Bigs.” In both, ERAs far below the revered 3.00 accompanied his double-digit winning records. Simultaneously, he enjoyed a warm relationship with the Pirates’ most famous player, one of baseball’s all-time greats, Honus Wagner, Hall of Fame shortstop. The two were “fishing buddies” and “clean livers,” and superb examples to teammates and fans that drinkers and late-hour carousers did not dominate Pittsburgh’s roster.

But the team’s ownership cared little about Rube’s potential and friendships. National-League cellar-dwelling St. Louis supposedly supplied talent capable of providing immediate improvement in Pittsburgh’s league standing, and Rube was among the five Pirates sacrificed in the trade. Christmas 1913 was hardly joyous for the hurler who the St. Louis Post-Dispatch demeaningly announced “lives in the tall grass of Arkansas, eight miles from civilization.”

Squabbles about salary, pitching assignments, and sore arms failed to endear Roberson to diminutive lawyer-turned-manager Miller Huggins, the Cardinals’ controversial “Mighty Mite” and “Mite Manager.” After two mediocre seasons (but each with a creditable ERA!), Rube found himself back in the minors. His stay in the National League was ended.

Yet he would have no part of San Francisco, where St. Louis had placed his contract. Refusing the reassignment, Roberson, predictably, opted to return to Floyd. He held his ground, worked his magic, and by July, in a Little Rock Travelers’ uniform, was again pitching “near home.”

The abbreviated season saw him register an 11 and 1 win-loss mark, with a 2.38 ERA, and the Cardinals indicated they wanted him back. But Rube was not to be moved. Finally, St. Louis gave up their quest for his signature and sold his contract to Little Rock. Thus began thirteen seasons of major-league pitching for minor-league wages, all because a Rube wanted to play in the Natural State.

Five times he won 20 or more games, and throughout the league, the Southern Association, he was a fan favorite, commonly available to josh with those who knew that in his prime, he was a flame thrower, but with the years had morphed into a cunning lefty. He would consistently earn a laugh from young and old alike when he agreed that he always commanded three pitches: slow, slower and slowest.

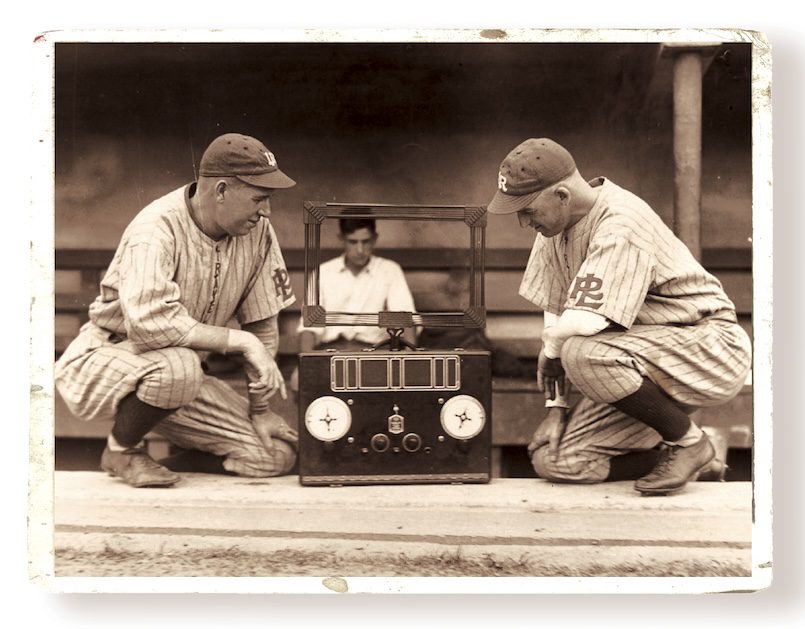

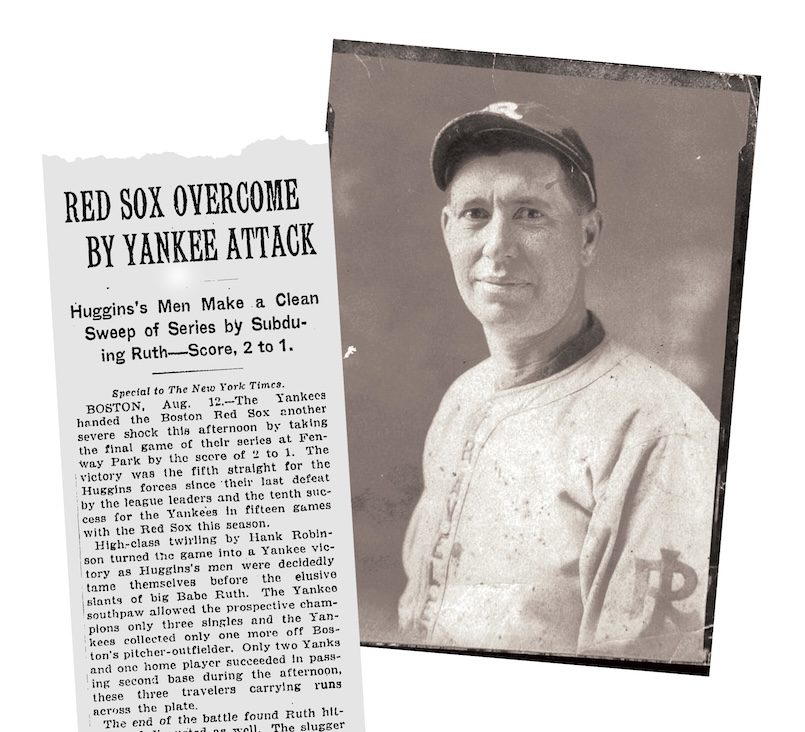

In 1918 came the highlight of his 21-year career. With the Southern Association season ending early because of World War I, Rube joined the New York Yankees at the request of his one-time nemesis Miller Huggins, now managing the Bronx Bombers. On Aug. 12, in Fenway Park, he bested baseball’s most famous player ever, Boston Red Sox’s Babe Ruth, two to one, surrendering just three hits.

Such excellence deserves every Arkansan’s respect.

The New York Times article covers a game Roberson pitched in August 1918 against Babe Ruth, who was the pitcher for the Boston Red Sox early in his career. Roberson pitched all nine innings, winning 2-1, with Ruth popping up for the final out. “Rube considered it the highlight of his major league career,” said his grandson, Fred Roberson of Little Rock. He had been called up by the Yankees after the Southern Association shut down in May 1918 due to so many players leaving for World War I.

Miller Huggins, who managed the Cardinals during his two years there and whom Roberson disliked, was now managing the Yankees. Rube left the team in August and returned home to Arkansas, refusing to report to the Yankees in 1919. Eventually, he was released to play for the Travelers again for another 10 years or so.

- Celebrating Athletic Excellence: Lonoke County’s Eddie Hamm - September 30, 2024

- Celebrating Athletic Excellence: Conway County’s Bud Mobley - September 8, 2024

- Celebrating Athletic Excellence: Cleburne County’s Keith Cornett - July 31, 2024