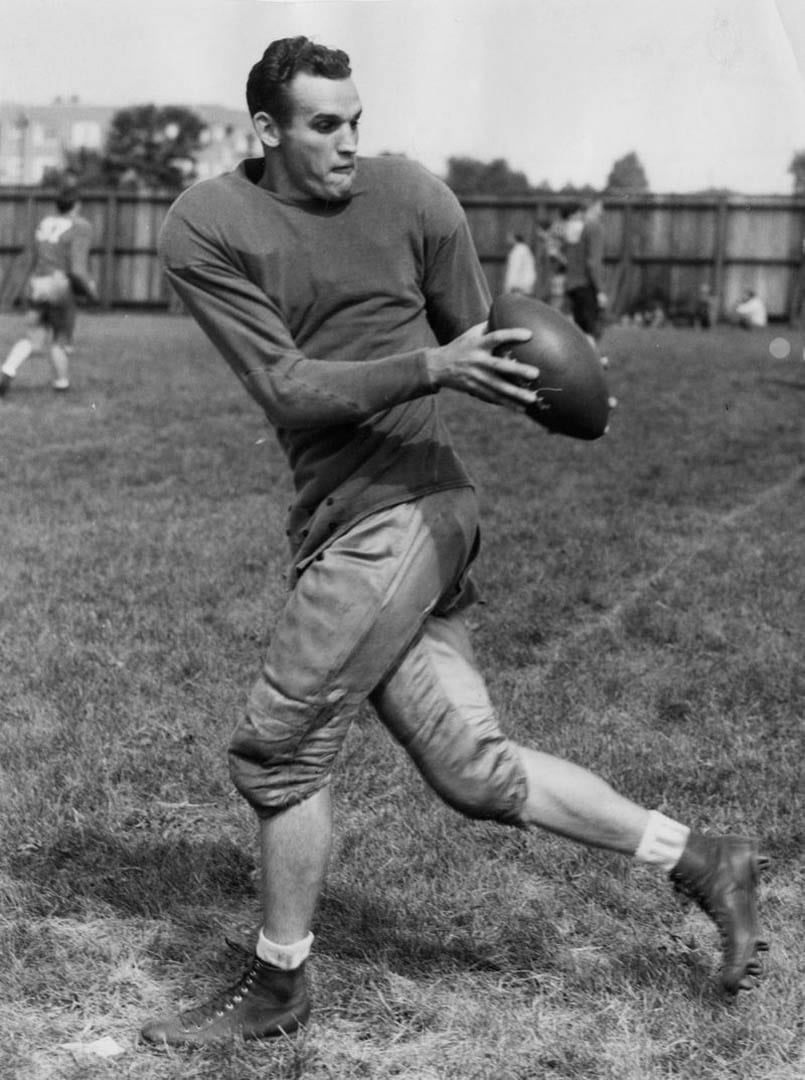

31 Jan 2021 Celebrating Athletic Excellence – Pulaski County: Ken Kavanaugh

By Dr. Robert Reising

One of the nation’s most spectacular pass receivers ever, Ken Kavanaugh, was more than simply an outstanding football player. He was a multi-sport luminary who, in addition to meritoriously serving America in wartime, enriched the nation’s sports landscape for more than half a century. Arkansas has produced few athletes with a greater claim on respect, national as well as state.

Ken was born in Little Rock on Nov. 23, 1916, the youngest of three children. His father was a railroad machinist and his mother a homemaker whose brother founded the popular Schmand Candy Co. Like his brother and sister, in his first years Ken knew only middle-class American values, honed on Depression-era deprivations. Hard work, courage, and confidence burgeoned into lifetime strengths.

Those strengths impressed area sports fans. By high school, he had emerged as a gifted performer in virtually every athletic endeavor he attempted. He earned a host of honors, including selection to All-State basketball and football teams before graduating from Little Rock Central High in 1936. Immediately, he continued his award-winning career at Louisiana State University (LSU). On the diamond, he excelled as a high-average batter with “pop” in his bat. The exceptional speed obvious in his track achievements provided a third plus. His play at first base was likewise eye-catching, his agility and quick hands teaming with his 6-foot 3-inch frame to equip him with ideal defensive skills.

In football, his physical assets also served him handsomely. In Little Rock and Baton Rouge, he played on defense as well as offense. And weighing over 200 pounds, Ken outmuscled, as well as outjumped and outran, many an opponent. Yet for him, pass catching was also “a thinking man’s game,” and he scored more than a few touchdowns by setting up and faking out opponents.

At LSU, because varsity athletics permitted no freshmen, he compressed one of the most storied Tiger careers into just three years. In 1937, he earned second team All-Southeastern Conference (SEC) honors on a 9 and 2 Sugar Bowl team, graduated to first team All-SEC the following fall, and reached unqualified national excellence in his final campaign. In 1939, he repeated his SEC honors of the preceding year while adding SEC Co-Most Valuable Player (MVP), Consensus All-American, the Knute Rockne Memorial Award, the Touchdown Club’s “Lineman of the Year” Award, the Blue-Gray Classic’s MVP, and (although not a back) seventh place in the Heisman Trophy voting.

Unfortunately, months passed before he learned he had gone “high” in professional football’s draft. Acting immediately, however, was baseball’s St. Louis Cardinals executive Branch Rickey, later famous for breaking major league baseball’s color line by signing Jackie Robinson. Convinced baseball held Ken’s future, he lured him into signing a contract and assigned him to Kilgore in a Class C Texas league. Deep into a successful season, however, Ken learned of his National Football League (NFL) drafting, immediately negotiated his Kilgore release, and after performing in the College (football) All-Star Game, joined the Chicago Bears for a salary paying him “better than anyone else in the league.”

Clearly, he was a precious two-sport commodity commanding the league’s most lucrative reimbursement. He starred for eight NFL seasons, cushioned around three years (1942-44) of action-packed, commendation-winning service as a World War II bomber pilot in Europe. He helped the Bears win 72 percent of their games and NFL championships in 1940, 1941, and 1946, scoring a touchdown in each of the three title wins. He twice led the league in yards-per-pass reception, once before and once after the war, and he twice led the league in touchdown receptions, once with a team-record 13, a number enwrapping another team record, a touchdown reception in seven consecutive games. His 50 touchdown receptions allow him another Chicago first, just one short of the NFL record.

Retirement from the playing field in 1950 was followed, first, by coaching stints with the Bears and at Boston College and Villanova and, then, by 45 years of coaching and scouting for the NFL’s New York Giants. Ken became “a revered member of the Giants’ family … [for whom] he made many important contributions … over the years,” said John Mara, team president and CEO, after the 2007 death of the bomber “pilot … [with] nerves of steel.”

Another “revered member of the Giants’ family” was a fellow scout, African American Rosie Brown, the team’s Hall of Fame tackle with whom Ken had “an inseparable bond.” The special friendship receives insightful attention in “The Humility of Greatness,” Ken Jr.’s tribute to his father. Also illuminated in the biography are the inspiring feats of a man deserving limitless respect in Pulaski County and the 501.