30 Nov 2020 Celebrating Athletic Excellence: Lonoke County – Eddie Hamm

By Dr. Robert Reising

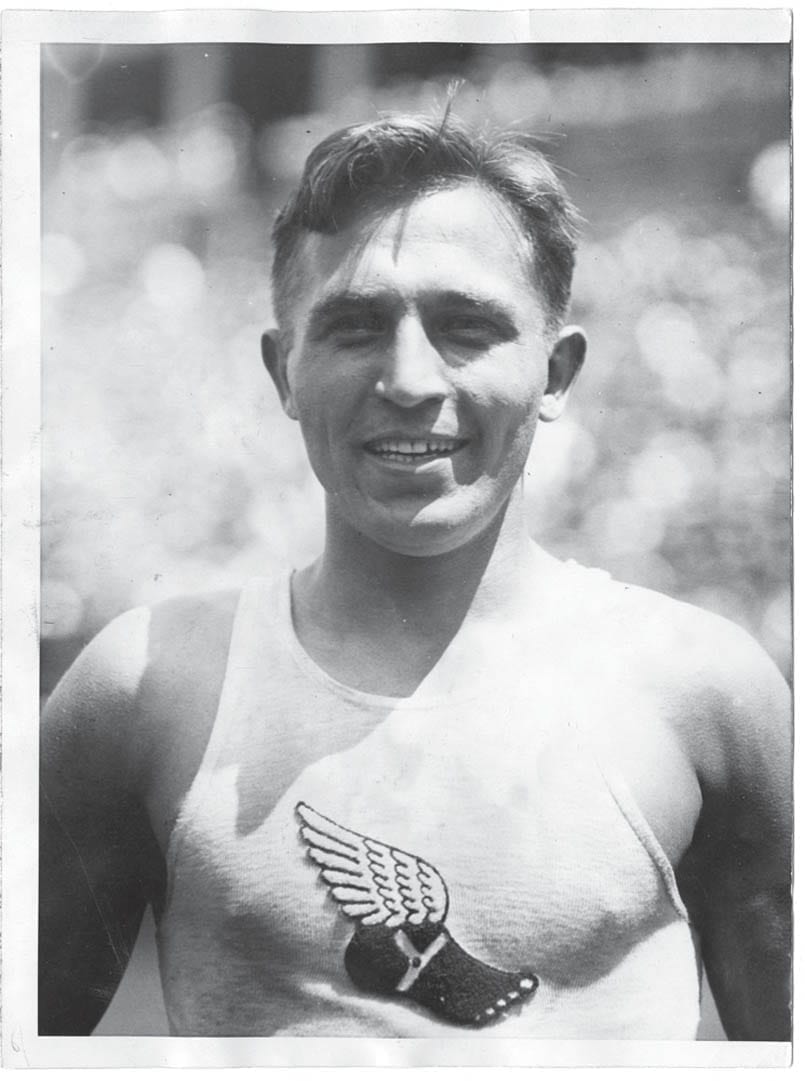

At age 22, he was the world’s best. Overcoming a debilitating disease, he had catapulted through more than two decades with incomparable competitiveness, increased ability and consistent success to emerge the globe’s premier long jumper. In 1928, Eddie Hamm brought unprecedented respect to himself and his native state as Arkansas’ first Olympic gold medalist.

A Lonoke home of modest means welcomed him on April 13, 1906. In subsequent years, Charles Hamm, a plumber and electrician, and Zilpah Hamm, a housewife, welcomed five other children, one a female. None of the quintet, however, revealed the athletic potential Eddie seemingly possessed at birth. Nor did vastly different challenges fail to fascinate him. By junior high school, his peers sensed a unique multisport marvel in their midst.

With increasing frequency and intensity, bouts of malaria intruded. Absences from classes and practices threatened to become the norm along with fevers and fatigue. Yet, he persevered. A four-year star for the high school football team, Eddie attracted special luster with his flawless field-goal record. In track, comparable excellence allowed him to claim the state long jump for three consecutive years, including a state record of 23 feet 2 inches in the first year; the 220-yard dash for three years; and the 100-yard dash for two years. In his senior year, he did not settle for just three firsts in a single meet. At a University of Arkansas invitational, he won four: the 100-yard dash, the 200-yard dash, the long jump, and the high jump. In the previous year at a Lonoke gathering of 20 schools, Eddie had also claimed four wins, but only three were in senior track. The fourth had come in declamation, one of the literary events held in the high school auditorium. He earned the state title a few weeks later.

The Georgia School of Technology, now Georgia Tech, beckoned. A scholarship allowed Eddie to enroll in the fall of 1925, and he promptly appeared in football togs for preseason photographs and practice. Only a few days passed before athletic department authorities intervened, forbidding further gridiron participation because of their fear of injuries. Eddie’s football career was over, but his most spectacular track years lay ahead.

Those years brought him headline-making success in the United States and later overseas. For three consecutive years, 1926 through 1928, the 5-foot 11-inch, 170-pounder seized first place in three events in Southeast Conference (now the Southeastern Conference) tournaments: the 100-yard and the 220-yard sprints and the long jump. In 1928, he broke the conference record in the long jump with his 25 feet 6 3/4 inches mark and triumphed in the national meet. In the subsequent Olympic trials, his leap of 25 feet 11 1/2 inches earned him not only a trip to Amsterdam, Holland, but also the world record in the long jump. He was prepared for Olympic gold, and on July 28, 1928, he seized it with yet another record-breaker: an Olympic-best long jump of 25 feet 4 3/4 inches.

With Georgia Tech and a grateful nation awaiting his return, Eddie, joined by several Olympiad teammates, toured England and Germany. Lonoke’s finest won the long jump in every meet. But misfortune loomed on the horizon, personal as well as global. Appendicitis hospitalized him within weeks of his return to America on the eve of the devastating worldwide Great Depression. In 1931, after being elected president of the Student Council, he reluctantly concluded that competing and bettering his Olympic mark in the 1932 Olympiad would be impossible as he was slow to regain his strength and agility.

He was never to appear in another Olympiad. In Adolph Hitler’s 1936 “Nazi Olympiad,” Eddie had no opportunity to challenge the iconic Jesse Owens, who set a new long-jump best with a leap of 26 feet 5 inches. His chances to rewrite Olympic history had disappeared with the Depression’s crushing impact upon Arkansas’ economy. A post in Oregon with Atlanta-based Coca-Cola offered the commerce graduate a more promising future.

His decades-long, multi-position career with the beverage corporation flourished, first in Klamath Falls and later in Bent. At the height of his success, however, 44 months of wartime military service interrupted, taking him to a variety of foreign nations as a major. At war’s end, he rejoined Coca-Cola, and emphysema later forced him into retirement in scenic Albany, Oregon. He died there on June 25, 1982; his ashes later scattered over his beloved Clear Lake.

Twelve years earlier, he had donated his trophies to Georgia Tech. Today, Lonoke County and the 501 remain proud of that award-winning native son.